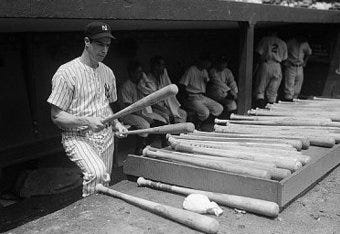

“I believe anybody who is not afraid to fail is a winner.”

- Joe Torre, Major League Baseball player, manager, administrator, and member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Part III of a Five-Part series titled: “Beyond Silos: The Power of Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration”

Baseball is a game of failure.

The best hitters who are enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York typically have a career batting average right around .300, give or take a few percentage points.

Think about that: the most talented baseball professionals failed their task seven out of every 10 attempts and are considered the best to ever do it. In what other industry can we fail so much and be considered hall of famers?

Baseball—as is life—is riddled with failure. I can make the argument that we fail every day on some level. From micro-failures that we hardly notice, to macro-failures that we need to mend. Insignificant failures to magnificent failures. Failures that affect only us to failures that affect those around us.

Like baseball players, we should embrace failure as something that is inevitable and not let the fear of failure inhibit us. Failing forward—applying lessons learned by making the appropriate adjustments—is a superpower.

Big, multi-stakeholder initiatives rarely fail because the idea was too small. They do so because the operating system—mandate, governance, coordination—can’t carry the weight. When decision rights are murky, when no one owns the “grey area” between teams, and when consent and measurement are afterthoughts, momentum leaks and credibility erodes.

This article will examine failures—of the macro sort!—in multi-stakeholder initiatives, what we can discern from them, and practical fixes you can put in place before the next steering call.

Patterns That Sink Coalitions

The first, and most obvious, barrier that collaborative efforts meet is unclear mandates with similarly unclear decision trees or decision makers. A double whammy!

Bold goals are established and announced publicly yet participating stakeholders each hold their own unique perspectives of what success looks like. Decisions are made yet revisited frequently, and scope of work expands without consensus or understanding from each team. You see this often in post-mortem reviews where independent auditors point to fractured authority as the root cause: multiple boards, agencies, or vendors pulling in different directions with no single line of accountability.

Last week’s focus was on the value of a neutral, third-party integrator at the core of every successful collaborative initiative, which is an easy segue to the second barrier to success: not having an integrator directing traffic in the middle of it all.

Complex coalitions aren’t just a bunch of tasks; they’re handoffs and coordination around who’s doing what.

When nobody owns interfaces, testing, readiness gauges, and the decision cadence, risks surface too late for recovery and transitions are dropped in the middle of chaos. The most public example of this dynamic came during the first launch of HealthCare.gov, where federal watchdogs cataloged weak planning and oversight across dozens of contracts and, critically, no lead systems integrator before go-live, a gap that was only filled after the crisis.

A third barrier is unrealistic risk allocation and political timelines. Public-private partnerships and megaprojects often push risk to the party with the least control, while delivery schedules are tethered to headlines rather than readiness.

Governance must be recalibrated when complexity spikes. Otherwise, stakeholders miss early warning signs and assurance becomes performative. Crossrail’s resets and governance changes near the finish line are a vivid reminder of what it takes to steady a late-stage program when integration risk has been underestimated.

Trust and consent, when taken for granted, pose a barrier that one often cannot come back from especially in the public light. If people believe a certain stakeholder is driving a collaborative effort for selfish purposes, or if transparency isn’t valued, the political economy shifts against you quickly.

Finally, dashboards that celebrate activity rather than outcomes is something I call ‘measurement theater.’ Showcasing activity can be done correctly, but it can too easily be a trap for showing work with no results. All bark, no bite. A collaboration without a performance-to-outcome metric winds up busy but light on outcomes that move the needle. In high-performing systems, performance is part of an equation that translates to outcomes.

Case Studies: Real Collaborations That Faltered (and What to Learn)

HealthCare.gov Launch (U.S., 2013): complexity without a conductor

The federal marketplace launched into a tailspin—users could not access the site, costs ballooned, and key functions weren’t ready. The Government Accountability Office and HHS Inspector General point to ineffective planning and oversight across a sprawl of contracts. A key miss: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) did not put a lead systems integrator in place before launch, leaving no one accountable for end-to-end integration until after the crisis, when CMS hired one to stabilize the program.1

Cover Oregon (U.S., 2013-2014): no single point of authority

The state exchange never processed online enrollments and eventually shut down. The independent First Data assessment and subsequent legislative reviews highlighted the same fault line: no system integrator and no single point of decision authority. Governance was fragmented across boards, agencies, and vendors, with change control and testing left to drift.2

Crossrail-Elizabeth Line (U.K., pre-2022 opening): integration underestimated

Sponsors and delivery teams repeatedly underestimated the remaining work to reach operational readiness. The National Audit Office and later “sponsorship lessons” reports document governance adjustments and independent assurance brought in to finish the job. The program ultimately opened, but only after leaders reshaped oversight and decision-making to match the complexity of late-stage integration.3

Phoenix Pay (Canada, 2016): a pay system that paid the price

The government-wide payroll modernization rolled out despite known defects, triggering years of pay errors for hundreds of thousands of employees. Canada’s Auditor General labeled it an “incomprehensible failure of project management and oversight,” and parliamentary committees catalogued how governance and change control broke down across departments.4

Columbia River Crossing (U.S., bi-state bridge, canceled 2013): multi-sovereign without mechanisms in place

A major interstate bridge replacement effort fell apart for lack of a durable bi-state authority and shared decision mechanisms. Oregon’s Secretary of State issued an advisory report summarizing lessons and recommending stronger joint governance modeled on successful multi-state authorities.

These case studies differ in sector and scope, but their fault lines are similar. Each lacked a clear center of gravity with authority to orchestrate decisions, guard interfaces, and hold the schedule to readiness.5

Applying Lessons Learned From Failed Collaborative Efforts

- Name a sole person in charge

- Make the mandate visible

- Adopt readiness gauges and revise if needed

- Measure for progress, not theater

- Staff for the season you’re in

Ambitious collaborations fail in familiar and similar ways.

Mandates blur, centers wobble, calendars outrun readiness, consent doesn’t solidify, and dashboards that become just noise. But they also succeed in predictable ways. Documented mandates, named integrator, realistic decision gauges, and measurements that reflect outcomes.

If you are about to launch, or rescue, a collaborative initiative, start with the simplest move: put someone in the middle, write down what they own, and hold the calendar to its readiness gauges. The rest of the system will begin to feel like a lighter lift for all involved.

That’s how complexity turns into momentum you can rely on. Inside your organization, with your fellow partners, and in the eyes of the people you serve.

Next in the series:

Building for Success: how to design coalitions that endure and compound impact. (Release date: 9/15/25)

Thanks for reading The Fractional Advantage! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

1 U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2014, July 30). Healthcare.gov: Ineffective Planning and Oversight Practices Underscore the Need for Improved Contract Management. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-14-694

2 Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. (2016, May 25). How Mismanagement and Political Interference Squandered $305 Million Federal Taxpayer Dollars. https://oversight.house.gov/release/20941/

3 National Audit Office. (2021, July 9). Crossrail - a project update. https://www.nao.org.uk/reports/crossrail-progress-update/

4 Office of the Auditor General. (Fall 2017). Phoenix Pay Problems. https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_oag_201711_01_e_42666.html

5 Oregon Audits Division. (February 2019). Advisory Report: The Columbia River Crossing Project Failure Provides Valuable Lessons for Future Bi-State Infrastructure Efforts. https://sos.oregon.gov/audits/Documents/2019-07.pdf